- Home

Page 3

Page 3

One Blood Ruby

One Blood Ruby Desert Tales

Desert Tales Faery Tales & Nightmares

Faery Tales & Nightmares Enthralled: Paranormal Diversions

Enthralled: Paranormal Diversions Wicked Lovely

Wicked Lovely Made for You

Made for You The Maiden Thief

The Maiden Thief Two Lines

Two Lines Seven Black Diamonds

Seven Black Diamonds Love Struck

Love Struck Guns for the Dead

Guns for the Dead Radiant Shadows

Radiant Shadows Ink Exchange

Ink Exchange Darkest Mercy

Darkest Mercy Stopping Time and Old Habits

Stopping Time and Old Habits Carnival of Secrets

Carnival of Secrets Carnival of Lies

Carnival of Lies This Fond Madness

This Fond Madness Graveminder

Graveminder The Arrivals

The Arrivals Awakened: A New Twist on a Timeless Tale

Awakened: A New Twist on a Timeless Tale Cold Iron Heart: A Wicked Lovely Novel

Cold Iron Heart: A Wicked Lovely Novel Summer Bound: A Wicked Lovely Story

Summer Bound: A Wicked Lovely Story The Wicked & The Dead (Faery Bargains Book 1)

The Wicked & The Dead (Faery Bargains Book 1) Dark Court Faery Tales

Dark Court Faery Tales of Maidens & Swords

of Maidens & Swords Of Roses and Kings

Of Roses and Kings Pretty Broken Things

Pretty Broken Things Enthralled

Enthralled Rags & Bones

Rags & Bones Ink Exchange tf-2

Ink Exchange tf-2 Stopping Time

Stopping Time Tales of Folk & Fey

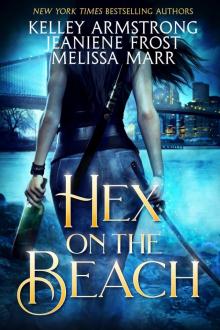

Tales of Folk & Fey Hex on the Beach

Hex on the Beach Wicked Lovely Free with Bonus Material

Wicked Lovely Free with Bonus Material Wicked Lovely tf-1

Wicked Lovely tf-1 Wicked Lovely with Bonus Material

Wicked Lovely with Bonus Material Carnival of Souls cos-1

Carnival of Souls cos-1 Radiant Shadows tf-4

Radiant Shadows tf-4 Darkest Mercy tf-5

Darkest Mercy tf-5 Carnival of Souls

Carnival of Souls Desert Tales: A Wicked Lovely Companion Novel

Desert Tales: A Wicked Lovely Companion Novel Fragile Eternity tf-3

Fragile Eternity tf-3 Old Habits

Old Habits Stopping Time, Part 2

Stopping Time, Part 2 Stopping Time, Part 1

Stopping Time, Part 1